Howie Cohen spent more than 50 years reshaping how bicycles were made and sold around the world

PHOTOS: TODD VAN FLEET

Howie Cohen was not a man on a mission. He was a man with a passion — for bicycles. Anything and everything bicycles. And he had, by any measure, been wildly successful in the bicycle business. But today, a look back at what Howie accomplished is amazing. Even at 74, Howie the Bikeman was working seven days a week cataloging his life of bicycles one shower curtain, lighter, piece of vintage sheet music, drinking glass and set of cuff links at a time.

“I fall in love with every bicycle item I touch.”

Looking back on and savoring a career rich in memories and relationships — a life spent buying, selling, fixing, painting and supplying two-wheeled machines the world over — Cohen was, in a sense, reliving his storied past with every storage box full of bicycle knickknacks he opens.

“I fall in love with every bicycle-related item I touch,” Cohen said as he lifted the lid on one of the hundreds of file boxes filled with bicycle mementos that fill his sizeable Lafayette, CO, basement to the ceiling. “It’s like Christmas every day around here. When I touch something, I usually remember where and when I bought it and who I bought it from (or who gave it to me). It brings back warm memories.”

Given the life Cohen has lived, the changes he has seen and the revolution he sparked in the bicycle industry around the world, one would think he should have written a book. But in a way, his ongoing effort of cataloging his collection – truly, a world-class museum in the making – on his Web site (howiebikeman.com) is just as good, if not better.

Start ’em young

Cohen’s passion for bicycles was tied closely to his father, Leo, who, during the depths of the Great Depression, was scratching out a living selling magazine subscriptions door-to-door in Minneapolis, MN. Before Howie was born in 1939, Leo was buying clunker bikes for $5 so his brother-in-law could fix them and re-sell them for $10.

Leo bought into his brother-in-law’s business. It grew and he sold back his interest in 1946. Leo bought a house trailer and moved Howie, his younger brother, Leo Jr., sister, Louise (aka Puss) and mother, RosaBelle, to Los Angeles. There Leo bought a bicycle store at 168 N. LaBrea Ave., named it Playrite Bicycle Supply Co. and an empire was born.

Gentle, well-spoken and enthusiastic, Howie Cohen relished telling stories about his early days in the shop with his dad. It was under his tutelage that Howie not only fell in love with the two-wheeled machines, but learned all aspects of the bicycle business that he would grow to dominate.

“My brother and sister and I were brought up in that store,” Cohen said. “That’s all I knew. When I was eight, I was allowed to dust the bikes. At nine or 10 I could sweep the floor. When I was 11, I started working in the repair department and would fix flats and paint bikes. The last year of our retail business, I painted about 2,000 bikes.”

“It happened pretty fast, faster than we could handle it”

Along the way, Playrite was changed to West Coast Cycle Supply Co. (a.k.a. WCC) to reflect the switch from retail to wholesale. Leo died when Howie was 23, and his death struck Howie hard. He had finished school and was well on his way to making big waves in the bicycle business, but his mentor, friend and father was missed terribly, and is to this day.

In the early ’60s, business at WCC remained very much a family affair. As Cohen writes on his Web site, “The entire family assisted dealers who came in to purchase and pick up their orders; good service to customers was the top priority.”

Growing global

The wholesale business grew rapidly, thanks in no small part to Howie’s integrity, hard work and outside-the-box thinking.

“Howie was very much a visionary,” said Pete Mole, general manager for U.S. operations for Dahon California, the largest manufacturers of folding bicycles in the world and a long-time friend and colleague of Cohen’s. “He developed markets that were unheard of. He didn’t mind traveling all over the world to find products that he could market in the U.S.”

“He was the first to venture to Japan,” Mole said. “He saw a country that was able to move in the right direction and improve on their products and at a price that would kill off the Europeans.”

While others shrugged off Japanese products at the time as being poorly made (they often were), Cohen was drawn to their manufacturing philosophy of Kaizen or “never-ending improvement” imported in the ’50s from U.S. industrialist Arthur Demming.

Cohen was among the first to forge deep and lasting personal and business relationships with what would become Japanese bicycle manufacturing royalty, including names like Shimano, SunTour, Kawamura, Taihei, Hatsune, Tsuyama, Kuwahara, Ishiwata and many others.

“He was an exclusive distributor for SunTour,” Mole said. “Wholesalers who wanted to use those brakes, shifters, pedals and things, had to go through him.”

Product placement pioneer

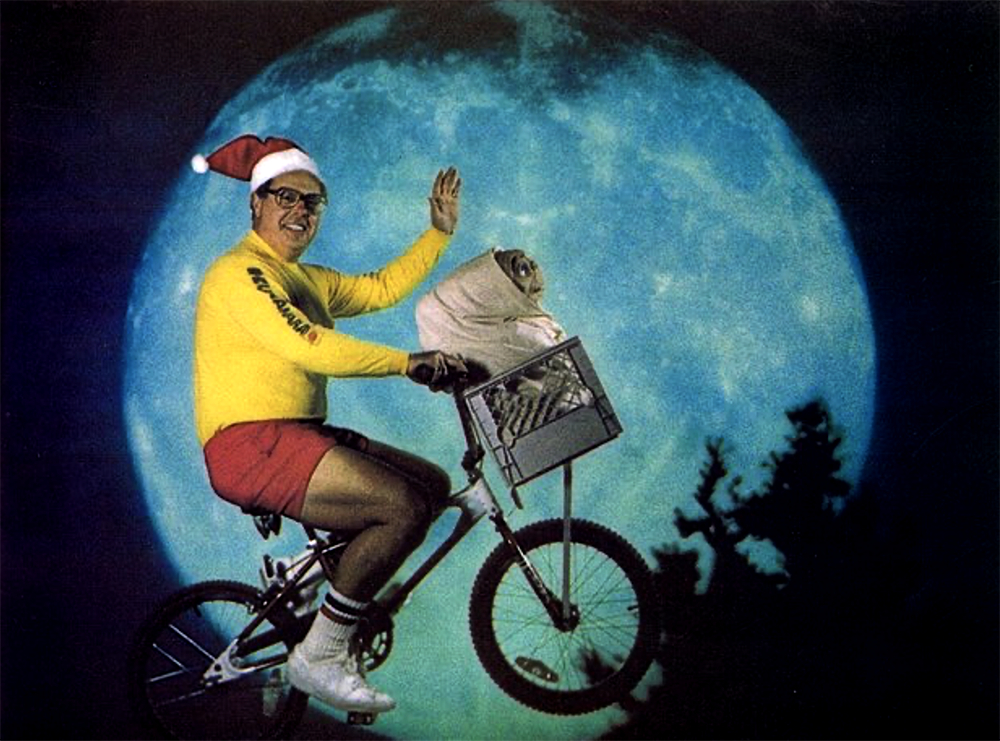

After selling West Coast Cycle Supply in 1976, Cohen launched Everything Bicycles and soon thereafter Kuwahara Cycle Co. asked Cohen to promote and market the Kuwahara brand the same way he did the Nishiki and Azuki brands. Kuwahara produced high-end BMX bikes that had become so popular that Universal Studios contacted Cohen and requested that he give them some two dozen Kuwahara BMX bikes for Steven Spielberg’s movie, “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.” This represents one of Cohen’s crowning claims to fame (and not a little trickle-down boon in sales).

In 1981, Cohen had never heard of anyone named Steven Spielberg, but was asked by Steve Adler, a vice president at Universal Studios, if he would give the maker of the recently released “Raiders of the Lost Ark” two dozen bikes (many, which at the time, retailed for about $600 each).

Cohen recalls saying: “Mr. Adler, every time I’ve gone to the movies, which isn’t very often, I’ve bought a ticket. So I think the movie, if they want to use our bicycles, ought to buy our bicycles. To which Adler replied, ‘I don’t think you understand.’”

Long story short, Cohen delivered the bicycles and the movie was made. In the aftermath of the wildly popular movie, Cohen sold “thousands” of ET3003 Kuwahara bikes that retailed for $260 a pop.

“It happened pretty fast; faster than we could handle it,” Cohen said. “They’re going for $1,200 to $1,500 a bike now.”

In 1989, Cohen sold the Kuwahara name back to the Japanese factory that was making them and “retired.” In the afterward he was doing consulting work for the likes of The Gary Fisher Bicycle Co., Avid and several others, but his true passion was in his boxes of “stuff.”

Cohen’s “full-time job” was cataloging his vast collection of bicycle memorabilia – tens of thousands of items (see side bar) – that fill a mountain warehouse and would be unparalleled fodder for a world-class bicycle museum.

“There are many things. I’m sure there are thousands of things that I don’t have, but I don’t know of them,” Cohen said. “I can’t even catalog all the things I do have.”

But every day that passed, he was getting closer and closer to finding out just what he did have. And thanks to his website, the world can share his love of bikes and all things bicycle.

Howard S. Cohen, passed away on July 11, 2013. He is missed by his family and friends, and his myriad of associates in the bicycle industry, Howie’s warm, generous spirit and tenacious love for life will be remembered by all who loved him and received his help and guidance over the years.